Reading sample (English) - Mars in Aries (1940)

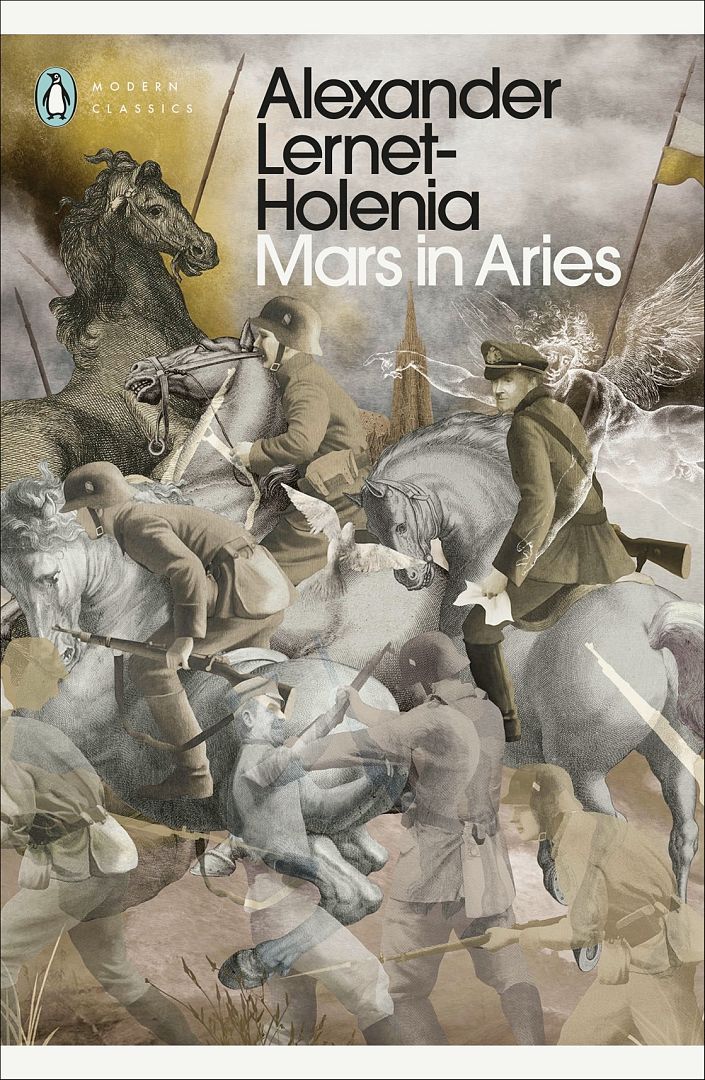

With his novel Mars in Aries, Alexander Lernet-Holenia processed his experiences during the Polish campaign of 1939. Although the S. Fischer Verlag had already printed 15,000 copies in 1940, distribution was blocked at the last moment by the Propaganda Ministry of the Third Reich, and the novel was therefore first published only after the war, in Stockholm in 1947.

The work is regarded as one of the most significant war novels in Austrian literature of the 20th century. There are also several compelling reasons to read Mars in Aries against the backdrop of the author’s own lived reality, under the lens of a poetics of hidden writing—in other words, as a novel of resistance. With haunting intensity, the author interweaves reality, dream, and symbolism into a narrative that portrays the inner conflict of human beings at war. The following excerpt offers a glimpse into this unique literary atmosphere.

Mars in Aries translated by Robert Dassanowsky and John S. Barrett, Penguin, London, 2025

Mars in Aries

(Extract)

A migration numbering in the millions was sweeping across Poland. It swept from west to east. It was made up of armies, those of the pursued and those of the pursuers, of fleeing supply columns and baggage wagons, of railroad trains that fled until they came to destroyed bridges or switch points that had been bombed – leaving railroad cars by the thousands stranded on the tracks – of horse- drawn carts whose teams were starving and dying, and of the innumerable vehicles of the columns clattering along after them, of tanks, of cavalrymen, of those on foot, in uniform and in civilian clothes, who’d been running for weeks, farther and farther away from the supply depots where the uniforms and equipment that they were supposed to have received had long since fallen into the hands of their pursuers, of disintegrating regiments of Poles, of deserters and looters, of men whose boots were hurting them and others who’d thrown away their boots and were walking on blistered feet, of the battered, sick, and wounded, of people from cities and towns, of country folk, all of them either being driven or dragged farther to the east by the fleeing armies – dishevelled, filthy, hungry, sleepless all of them, the pursuers as well as the pursued. Not a train was running any longer, not a horse was being fed, not a cow milked, cattle roamed around the smoking ruins of farms, bellowing. No communication existed – the enemy divisions had lost all contact with their army’s headquarters, the regiments with their divisions. Eventually only isolated groups put up any resistance. But again and again they were beaten and pursued, taken prisoner, their men crossed the lines, surrendered, deserted by the dozens, by the hundreds, by the thousands. To the left and the right of the roads the ditches were full of discarded weapons and ammunition, overturned field guns and vehicles. Dead horses with bloated stomachs fouled the air. In the vicinity of Rzeszow even a dead elephant was found in a ditch.

Not a windowpane was intact any longer, not a man was shaven, not a woman was combed, the cattle broke their legs running away, as if their bones were made of butter, villages seemed to go up in flames by themselves, there was no longer any food, no cigarettes, and nothing to drink. Even the crackled siphon bottles were nowhere to be found. Houses either stood empty or were bursting with refugees, no regiment was receiving rations any longer, prisoners reported that they had lived for days on what they’d begged from the farmers. But the farmers themselves had nothing any longer. All the ditches were full of rubbish; the entire country seemed as though it were decomposing while alive, out of a hundred soldiers not even ten were standing by their colours, it was the most unprecedented, or at least most precipitous, collapse of all time. And directing their rigid gaze at that chaos from city squares and streets were the statues of politicians and artists of times gone by.

Absolutely everyone had left their houses and dwelling places; by the millions the entire population was moving eastwards in turmoil, without luggage, without even the most basic food supplies, following vague orders or hopes. This went on until almost the middle of September. Thereafter, the entire chaotic flight turned westward again, away from the Russians, who in the meantime had also entered the war. Everything and everyone came streaming back, came to a standstill, then remained trapped somewhere between the Bug and the San rivers.

There, some of the Poles committed acts of true bravery as well. There were some, especially officers, who resisted to the end. But they didn’t know that they were already long lost. They’d been without real news for weeks and thought that farther to the north their armies had long ago reached Berlin . . . They had no inkling of the Russians’ advance as yet, they knew nothing at all. They thought they were victorious everywhere – yet two hours later they were being taken prisoner. Some, however, chose death over captivity, and of the officers of the troops who were running into the enemy in the east, hundreds shot themselves.

The entire catastrophe played out in blazing heat. There were days that were as hot as July, indeed, even hotter, it was as though the sun had erupted like a volcano and was devouring the earth with its fire. Not a drop of the rain that the Poles were so hoping for fell, that would have turned the ground into a morass in which the motorized columns would have stalled. Instead of that there was nothing but dust. It was yellowish on the paths through fields and bluish- white on the roads, with a sweet smell, a stench, especially at night. It was foot- deep, ankle- deep, knee- deep. As they crossed the San River – or actually as they were just approaching it – the dust was incredible. There were stretches of countryside, such as towards Wolhynia, where there was an ocean of dust, lying like liquid between rocky hills bleaching in the sun like bones of the dead. And where the rock was violet in colour, it seemed as though tendons were decomposing on top of it. The dust enveloped everything, it coated faces and uniforms in thick layers as if it had been sprayed like water, tiny particles penetrated into everything as if they’d been sucked in by capillary action, it got into watches, into the breeches of weapons, into the carburetors of the engines, so that the air filters had to be cleaned every few hours. The men wrapped rags around their rifles and tied cloths in front of their faces, their eyes became inflamed and absolutely everyone looked like a corpse lying under a layer of dust. In the vehicles it piled up as if ocean waves had deposited it like sand. It rose in gigantic clouds, it reared up like towers, it became as dense as thunderstorms. It drifted over the entire land like veils from which it drizzled down like rain. It was impossible to eat without grinding it between one’s teeth, impossible to touch anything without first touching dust, it was as though it was being held up to mankind that they themselves were merely dust, nothing but dust.